Exploring the Magic of Discworld: Terry Pratchett’s Fantasy World

In the often bewildering tapestry of literary fantasy, few creations are as audaciously imaginative as Terry Pratchett’s Discworld.

Perched precariously on the backs of four cosmic elephants, which in turn stand atop the shell of a colossal turtle (Great A’Tuin, for the uninitiated) swimming through the vastness of space, the Discworld presents a universe that is as bizarre as it is boundless.

A flat world, where physics is not so much a set of rules but more a set of guidelines, and where magic not only exists but often has a mind of its own.

The brilliance of Discworld lies not just in its unique geography, but in the way it mirrors, mocks, and mangles our own world.

Here, in this whimsical realm, Pratchett managed to skewer every aspect of human society – politics, religion, technology, the arts, and even the mundanity of daily life – with a deftness that leaves one both tickled and thoughtful.

It’s a world where dragons can be powered by swamp gas, where the city of Ankh-Morpork operates with an efficiency that is both terrifying and terrible, and where a suitcase might follow you around on hundreds of little legs.

In Discworld, the absurd becomes the norm and the conventional gets turned on its head.

Death, a skeletal figure with a fondness for cats and a curiously human moral compass, chats away in ALL CAPS, while the Librarian of the Unseen University, transformed into an orangutan, finds his new form quite convenient (though it’s considered impolite to bring up the ‘M’ word – ‘monkey’).

This is a world where the edge is a place you can visit (if you dare), where the world’s best worst wizard, Rincewind, can run away from danger faster than anyone can run towards it, and where witches don’t just ride broomsticks but wield a sort of common sense so uncommon it might as well be a superpower.

In the myriad streets of Ankh-Morpork, the clatter and clamour of progress marches along with the regal absurdity of Lord Vetinari’s tyrannical benevolence.

Elsewhere, the rambling, rustic wisdom of the Lancre witches challenges the very fabric of reality, and in the shadows, the secret societies and guilds go about their business, which often involves things best left unmentioned.

The Discworld is a microcosm, a satirical mirror held up to our own world, reflecting our follies and foibles in a way that’s as enlightening as it is entertaining.

Pratchett’s masterful storytelling, rich with wit and laced with a dark humour that twinkles like a star in a night sky full of flying elephants and spellcasting turtles, invites us to laugh at the world, and perhaps more importantly, at ourselves.

This magical disc, teeming with its unforgettable characters and their ludicrously logical adventures, is more than just a setting for stories.

It’s a testament to the boundless creativity of one of the greatest storytellers of our time, a place where every jest is a jewel, and every absurdity hides a truth.

So, hop on your broomstick, grab your luggage (yes, the one with all the legs), and let’s take a tour through the enchanting, bewildering, and utterly irresistible world of the Discworld.

Rincewind series

Ah, Rincewind. If the Discworld had a poster boy for existential dread laced with improbable survival, it would be this man.

A wizard (of sorts), Rincewind is a character who could trip over a pebble and inadvertently prevent a war between two great empires, or perhaps find himself in a dimension where pebbles wage wars against shoes.

He’s a walking, mostly running, embodiment of Murphy’s Law – if anything can go wrong for Rincewind, it will go wrong spectacularly.

The Rincewind series is a rollicking romp through the Discworld, featuring the most reluctant of heroes.

Armed with a singular spell that has taken residence in his head (unfortunately making it impossible for him to learn any other spells), Rincewind’s greatest talent lies in his ability to flee from danger at an astonishing pace.

This ‘talent’ leads him into a cavalcade of catastrophes from which he narrowly escapes, usually through no skill of his own.

Beginning with “The Colour of Magic,” we are introduced to a wizard so inept, so bewilderingly devoid of magical aptitude, that he becomes the perfect tour guide to the madness of the Discworld.

Accompanied by Twoflower, the Disc’s first ever tourist, and The Luggage, a chest with as many feet as it has homicidal tendencies, Rincewind’s escapades set the tone for the bizarre world we’ve stepped into.

In subsequent books, our perpetually perplexed protagonist finds himself in situations ranging from accidentally becoming a great wizard (albeit in a parallel universe) in “The Light Fantastic,” to exploring the Discworld’s version of Australia in “The Last Continent,” a place where the wildlife is as likely to kill you as look at you, and that’s saying something on the Disc.

Through Rincewind’s eyes, we encounter the Disc in all its glory – from the heights of the magical Unseen University to the distant Counterweight Continent.

His stories are a twisted mix of satire and silliness, with a dash of melancholic wisdom.

As he bumbles from one crisis to the next, often screaming, we get a ground-level view of a world where the rules are made up and the physics don’t matter.

Rincewind’s journey through the Discworld is not just a series of escapades; it’s a masterclass in how to survive a universe that seems fundamentally opposed to your existence.

He’s the underdog’s underdog, the hero who’d rather be anywhere but here, and yet, through his eyes, we see the heart of the Discworld – chaotic, unpredictable, and utterly, irresistibly alive.

In essence, Rincewind’s tale is a story of survival, of finding humour in the face of utter despair and absurdity.

His character may not have the depth of Granny Weatherwax or the complexity of Lord Vetinari, but in his own bumbling, cowardly way, he captures the essence of the Discworld – a place where logic takes a backseat, and the impossible is just another Tuesday.

The Witches series

In a world where broomsticks are a preferred mode of transport and cauldrons are not just for cooking, the Witches of Discworld stand tall – or, more accurately, they sit around a cauldron, sipping tea and dissecting the peculiarities of human nature.

The Witches series, a cackle in the dark, a knowing smile in the face of adversity, brings to life some of the most formidable and endearingly pragmatic characters in the Discworld.

Granny Weatherwax, with a glare that could curdle newt’s milk.

Nanny Ogg, who knows a song about hedgehogs or, well, anything really.

And Magrat Garlick, as wet as a drowned salad but with a heart of, if not gold, then at least a very respectable silver alloy.

These women don’t ride to war; they saunter into it, armed with headology more potent than any sword or spell.

Starting with “Equal Rites,” where a young girl named Eskarina Smith challenges the male-dominated wizarding establishment, we are plunged into a world where witches don’t cackle and poison princesses, but rather, they deliver babies, tend to the sick, and deal with those pesky supernatural nuisances that keep popping up.

They are the unsung, and often unwilling, heroes of their world, grappling with the mystical and the mundane in equal measure.

The series truly blossoms in “Wyrd Sisters,” where Pratchett’s parody of Shakespearean drama unfolds with a distinctly witchy twist.

Here, Granny, Nanny, and Magrat meddle in royal politics with as much reluctance as a cat being given a bath, but with significantly more success.

It’s Macbeth turned on its head, with a lot more practicality and far fewer hesitations.

As we venture further, in “Witches Abroad” and beyond, the stories delve into fairy tales and folklore, turned on their heads with a sharp twist and a knowing wink.

The witches travel to far-off lands, encountering vampire counts, phantom horsemen, and the odd godmother, turning every story you thought you knew into something unrecognizable, and invariably funnier.

Perhaps the crowning jewel of the series is “Lords and Ladies,” where the boundaries between worlds grow thin, and the witches must confront not only the eldritch creatures of elder times but also their own pasts, dreams, and regrets.

It’s here that Pratchett’s gift for combining the profound with the profoundly absurd shines brightest.

The witches of Discworld don’t do magic in the way the wizards do – no, that would be far too easy and far less interesting.

They do something much harder. They deal with people.

With a wisdom that’s as practical as it is peculiar, they navigate a world that is perpetually on the brink of disaster, steering it away from doom with a sigh, a spell, and a well-timed word of advice.

Through the Witches series, Pratchett weaves a narrative that’s as much about understanding human nature as it is about the magic of the Discworld.

It’s a celebration of the strength of character, the power of knowledge, and the importance of a good cup of tea.

In a world where the biggest battles are often fought in the smallest moments, Granny, Nanny, and Magrat – along with a host of other, equally memorable witches – stand as champions, not of glory and honour, but of common sense, compassion, and a stubborn refusal to back down when things get tough.

They might not always save the world in the most conventional way, but they’ll always make sure it’s still there for tomorrow.

Death series

In the gloaming of the Discworld, where shadows whisper and the fabric of reality grows thin, there strides a figure, cloaked in black, his skeletal hand gripping a scythe that gleams like a slice of cold night.

Death, the ultimate equaliser, the final punchline in the cosmic joke of existence, is not just a metaphysical concept on the Discworld but a character – and what a character he is.

The Death series introduces us to the Discworld’s most unlikely protagonist, a character who speaks in ALL CAPS and has a fascination for humanity that is as endearing as it is perplexing.

From his first appearance in “Mort,” where he takes on a hapless apprentice, to “Reaper Man,” where he faces his own existential crisis, Death’s journey is not just about the end of life but about the discovery of what it means to live.

Death, with his horse Binky and a domestic life oddly reminiscent of a suburban sitcom, navigates the intricacies of human emotion and confusion with a sort of innocent bemusement.

In “Soul Music,” he grapples with the concept of music with rocks in, and in “Hogfather,” he steps into the rather large shoes of the Discworld’s version of Santa Claus, bringing a whole new meaning to the phrase “season’s greetings.”

But it’s not all existential musings and comedic misadventures; there’s a depth to the Death series that goes beyond the surface humour.

In “Thief of Time,” we explore the nature of time itself, with Death playing a crucial role in the balance of the universe.

Here, Pratchett’s wit is at its sharpest, cutting to the heart of what it means to be mortal, to fear, to hope, and to dream.

What makes Death such a compelling character is his unique outsider’s perspective on humanity.

He’s fascinated by us, by our quirks and contradictions, our capacity for great kindness and terrible cruelty.

Through his eyes, we see ourselves reflected back, not just in our final moments, but in all the chaotic, glorious mess of living.

In these books, Pratchett turns the concept of death on its head.

Here, Death isn’t just the end; he’s a character with his own arc, his own crises, and his own (admittedly quite dry) sense of humour.

He’s the Grim Reaper who loves cats, enjoys a good curry, and sometimes just wants to understand why humans do that strange thing they do where they move their lips and make sounds (talking, that is).

The Death series is a reminder that in the Discworld, everything has a different angle, a hidden depth, and that even in the darkest shadows, there’s room for a bit of light, a bit of humour, and a lot of heart.

With his scythe in hand and a bemused twinkle in his eye sockets, Death not only reaps souls but sows a rich tapestry of stories that challenge our perceptions and tickle our imaginations.

In a world teeming with life in all its absurdities, Death stands as a constant – a reminder that every end is just a new beginning, especially on the Discworld.

City Watch series

In the grimy, bustling, and perpetually smoky streets of Ankh-Morpork, amidst the din of clanging swords and the sharp retort of crossbows, there’s a force that tries to impose some semblance of order – the City Watch.

The City Watch series is a foray into the underbelly of the Discworld’s most notorious city, a journey through the cobbled streets and dark alleys where danger lurks around every corner, and so does a good kebab shop.

Leading this ragtag band of misfits is Sam Vimes, a man whose relationship with the gutter is both literal and philosophical.

Once a down-at-heels watchman, he rises through the ranks to become the Duke of Ankh, yet never loses his penchant for old boots and a finely aged bottle of scumble.

Vimes is a man of the people, mostly because he’d rather not be a man of the nobility.

“Guards! Guards!” is where it all begins – with a secret society, a dragon, and a plot to take over the city.

This book sets the tone for the series – a blend of crime, mystery, and a healthy dose of cynicism about human nature.

It’s here we meet the unforgettable characters that make up the Watch – Captain Carrot, a six-foot-tall dwarf (it’s a long story), Sergeant Colon, Corporal Nobbs (legally a human), and Angua, a werewolf who’s not only the sanest member of the squad but also has the best sense of smell.

Each book in the series builds on this foundation, turning the City Watch into something more than just a police force – it becomes a microcosm of the Discworld itself.

From the political intrigue and cultural clashes in “Men at Arms,” to the time-travelling conundrums of “Night Watch,” each story is an exploration of power, morality, and what it means to do the right thing, even when the right thing is as elusive as a straightforward tax form.

The Watch series is not just about solving crimes; it’s about navigating the complexities of a city teeming with trolls, dwarfs, vampires, and humans, all trying to coexist in the cauldron of Ankh-Morpork.

It’s about the thin blue line that separates order from chaos, a line that’s as blurred as Vimes’s vision after a night at The Mended Drum.

Underneath the humour, the chases, the narrow escapes, and Vimes’s grumbled philosophies, there’s a heart to these stories – a beat that resonates with the themes of justice, equality, and the fight against corruption.

Pratchett uses the City Watch to hold up a mirror to society, reflecting both its vices and virtues, its absurdities, and its moments of unexpected grace.

In “Thud!”, where tensions between the dwarfs and trolls reach boiling point, or in “Snuff”, where the goblin community’s plight takes centre stage, the Watch series delves deep into the murky waters of prejudice and fear, showing us that even in a fantasy world, the real monsters are often all too human.

The City Watch series is a testament to Pratchett’s genius in combining the fantastical with the profoundly relevant.

In these books, the clatter of a Watchman’s boots on the cobblestones is the rhythm of a city alive with stories, each waiting to be told with a twinkle in the eye and a hand on the hilt of a sword.

It’s a series that shows us that even in the darkest alleys, there’s a chance for redemption, for change, and maybe, just for a moment, for a bit of peace and quiet (until Nobby Nobbs shows up, that is).

Tiffany Aching series

In the rolling hills and ancient chalklands of the Chalk, under the watchful gaze of the standing stones, we meet Tiffany Aching – a young witch with a frying pan and a fierce sense of responsibility.

The Tiffany Aching series is a heartwarming and hilarious journey into the world of witchcraft, seen through the eyes of a pragmatic, no-nonsense heroine who’s wise beyond her years.

Tiffany is not your typical storybook witch.

There’s no cackling over cauldrons here; instead, there’s hard work, common sense, and a keen understanding of the human heart.

Starting with “The Wee Free Men,” we are introduced to Tiffany at the tender age of nine, as she sets out to rescue her baby brother armed only with a frying pan and accompanied by the Nac Mac Feegle – a clan of rowdy, blue-skinned, six-inch-tall pictsies with a penchant for fighting, drinking, and stealing.

As the series progresses through “A Hat Full of Sky,” “Wintersmith,” “I Shall Wear Midnight,” and finally “The Shepherd’s Crown,” we watch Tiffany grow from a determined young girl into a fully-fledged witch.

She learns the craft from the formidable Granny Weatherwax and the hilarious Nanny Ogg, dealing with everything from eldritch horrors to teenage romance with equal aplomb.

But the Tiffany Aching series is more than just a coming-of-age tale.

It’s a narrative rich with folklore, humour, and a deep understanding of the human condition.

Tiffany’s battles are not just with mythical beasts or the cruel, icy grip of the Wintersmith, but with the darker aspects of humanity itself – fear, ignorance, and cruelty.

The Nac Mac Feegle provide comic relief with their antics, but they also offer Tiffany a fiercely loyal support system.

Their battle cry of “Crivens!” and fearless (often reckless) approach to problem-solving often leads to hilarious and chaotic results, providing a perfect counterbalance to Tiffany’s more thoughtful and measured approach.

Pratchett’s genius in these books lies in his ability to weave profound themes into a tapestry of whimsical fantasy.

Each story is layered with meaning, exploring ideas of community, identity, and the power of belief.

Tiffany Aching’s journey is a testament to the strength of young people, to the wisdom that comes not from age, but from empathy and understanding.

The chalklands, with their ancient magic and timeless wisdom, serve as the perfect backdrop for Tiffany’s adventures.

Here, the land itself is a character, shaping and guiding Tiffany as she navigates the trials of both the mundane and the magical worlds.

In “The Shepherd’s Crown,” the final book of the series and Pratchett’s last, Tiffany faces her greatest challenge yet.

It’s a story of loss and legacy, of standing up and fighting not just for oneself, but for those who cannot.

It’s a fitting end to a series that has been as much about growing up as it has been about magic and mayhem.

The Tiffany Aching series, while aimed at younger readers, resonates with people of all ages.

It’s a reminder that sometimes, the most powerful magic we have is a kind heart, a sharp mind, and the courage to do what’s right – even when it’s hard.

In Tiffany Aching, Pratchett has given us not just a character, but a role model – someone who shows us that, no matter how small you are, you can make a big difference.

Moist von Lipwig series

In the labyrinthine alleys of Ankh-Morpork, where opportunity and treachery dance a dizzying waltz, there rises a star of dubious reliability but undeniable charm – Moist von Lipwig.

The Moist von Lipwig series is a delightful delve into the life of a con artist turned civil servant, a man as slippery as a greased eel and twice as cunning, tasked with dragging the city’s archaic institutions kicking and screaming into a new era.

Moist’s story begins in “Going Postal,” where he’s saved from the hangman’s noose by Lord Vetinari, Ankh-Morpork’s enigmatic ruler.

Given the choice between a swift drop and a stop, or reviving the moribund postal service, Moist, ever the opportunist, chooses the latter, thus embarking on a career of public service, laden with sarcasm and an undercurrent of existential dread.

Equipped with his wits, a golden suit, and a natural talent for deception, Moist breathes life into the dead letters and derelict post office, battling corrupt businessmen and sceptical public alike.

He’s a hero, not of noble birth or grand destiny, but of circumstance and an uncanny ability to talk his way out of (and occasionally, into) trouble.

In “Making Money,” Moist is coerced into overhauling the Royal Mint and the bank, a task riddled with economic absurdities and financial jargon turned on its head, showcasing Pratchett’s ability to make even the driest subjects hilariously absurd.

Moist navigates the labyrinth of high finance with the ease of a cat burglar, forever on the brink of disaster yet always one step ahead.

The series reaches its pinnacle in “Raising Steam,” where Moist is charged with the monumental task of bringing the steam railway to Ankh-Morpork.

It’s a tale of progress versus tradition, innovation clashing with deeply entrenched interests, all wrapped up in the smog and clatter of the locomotive era, Discworld-style.

Moist von Lipwig, as a character, represents the charming rogue archetype, but with a depth that comes from his constant grappling with his own conscience.

He’s a man who’s been given a second chance, and, perhaps begrudgingly, decides to make the most of it – not just for his own benefit, but for the good of the city that’s become his reluctant home.

Through Moist’s adventures, Pratchett explores themes of redemption, responsibility, and the nature of progress.

In a world that’s changing faster than a clacks message, Moist stands as a symbol of adaptability, resilience, and the enduring power of a good scam.

The Moist von Lipwig series, with its blend of satire, wit, and a dash of romance, is a testament to Pratchett’s ability to find humour and humanity in the most unlikely places.

In Moist, we find not just a con man turned good, but a mirror to our own world – a reflection of the chaos, the madness, and the sheer, unadulterated brilliance of progress and the people who drive it forward, one madcap scheme at a time.

Industrial Revolution series

In the smoky corridors and clanging workshops of Ankh-Morpork, amidst the buzz of newfangled ideas and the smell of progress (which suspiciously resembles the smell of burning), the Industrial Revolution series unfolds.

This collection of Discworld novels takes us on a rollicking ride through the Disc’s own version of an industrial age, where technology advances with all the grace of a one-legged troll in a dance contest.

The series kicks off with “Moving Pictures,” where the discovery of ‘clicks’ propels the Disc into its own peculiar version of Hollywood, dubbed ‘Holy Wood.’

Here, dreams are made and sold, and the boundaries between reality and illusion become as blurred as a vampire’s reflection.

It’s a tale rife with satire, poking fun at the absurdity of fame and the chaos of movie-making, where a starlet might be a talking dog and the greatest heroes are just a well-painted backdrop away.

“Reaper Man” follows, though it’s as much a part of the Death series as it is of the Industrial Revolution.

The focus here is on the repercussions of progress – what happens when even Death gets a pink slip?

The novel explores the theme of obsolescence, a poignant reminder that with every new invention, something old and familiar might just find itself out of a job.

“The Truth,” Pratchett’s ode to journalism, thrusts the printing press into the limelight.

William de Worde becomes Ankh-Morpork’s first newspaper editor, navigating a minefield of political intrigue, dwarfish typesetters, and a petulant talking dog.

It’s a world where the pen is mightier than the sword, provided the pen doesn’t run out of ink and the sword isn’t being wielded by a six-foot-tall dwarf with an axe to grind.

“Monstrous Regiment” takes a sharp turn into the world of war, following Polly Perks as she disguises herself as a man to join the army.

It’s a story about the roles we play, the masks we wear, and the monstrous absurdity of war, where the greatest battles are often fought with a well-placed word rather than a bullet.

Finally, “Raising Steam” brings us back to Moist von Lipwig, this time grappling with the steam engine and the railway.

It’s a tale of technological triumph, societal shifts, and the unrelenting march of progress, leaving footprints that look suspiciously like train tracks.

The Industrial Revolution series is a study in contrasts, a balancing act between the old ways and the new, magic and machinery, chaos and order.

These stories paint a picture of a world in flux, a Discworld caught between the comfortable familiarity of the past and the exciting uncertainty of the future.

It’s a place where a wizard might meet a robot, where a clacks tower stands tall next to a dragon sanctuary, and where change is the only real constant.

Pratchett, with his characteristic wit and wisdom, invites us to laugh at the absurdities of progress, to question the cost of advancement, and to wonder, perhaps, whether we’re not all just characters in our own version of a Discworld novel – where the next big thing is just around the corner, provided that corner isn’t eaten by a dragon first.

In the Industrial Revolution series, the future isn’t just bright; it’s a kaleidoscope of possibilities, each more bizarre and wonderful than the last.

Standalone novels

Ah, the standalone novels of Discworld – a smorgasbord of stories where Terry Pratchett, with the gleeful abandon of a wizard at a potion convention, delves into the nooks and crannies of his fantastical world.

These books are the literary equivalent of a day trip to the parts of the Disc you didn’t even know existed, each a unique gem that sparkles with Pratchett’s trademark wit and wisdom.

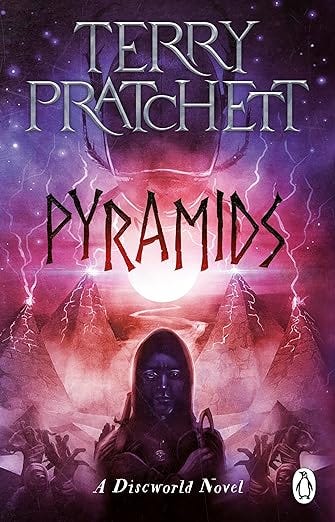

“Pyramids,” the tale of Teppic, a young assassin turned pharaoh, gives us a glimpse into the kingdom of Djelibeybi (a pun-laden version of Ancient Egypt).

Here, amidst the towering pyramids and a camel named You Bastard, Pratchett explores the quirks of time, tradition, and the hazards of having an architectural wonder as your resting place.

“Small Gods,” a divine comedy of sorts, delves into the life of the Great God Om, who finds himself trapped in the body of a tortoise.

This theological satire pokes fun at religion, belief, and the nature of divinity, all while following the hapless novice monk Brutha, who is the only one able to hear Om’s divine (and often cranky) voice.

In “Moving Pictures,” as mentioned earlier, we see the rise of the Disc’s version of Hollywood.

It’s a dazzling, dizzying look at fame and fantasy, where the silver screen holds more than just images and an intrepid band of characters must save the day, armed with nothing but their wits and a very keen talking dog.

“The Truth” takes a hard, humorous look at the world of journalism.

Through the eyes of William de Worde, the first journalist of Ankh-Morpork, we get a story filled with intrigue, murder, and the daunting task of navigating the truth in a city where the truth is often stranger than fiction.

“Monstrous Regiment,” part of both the Industrial Revolution series and a standalone, is a sharp satire on war, gender, and national identity.

Following Polly Perks and her ragtag band of soldiers, it’s a story about finding oneself, both literally and metaphorically, in the midst of chaos.

“Unseen Academicals,” kicks a football into the wizarding world of the Unseen University.

Here, the wizards must grapple with the advent of football, with all its fanfare and frenzy, revealing the absurdity and beauty of sports and their fans.

In “The Amazing Maurice and His Educated Rodents,” a tale for the younger (and young at heart) audience, Pratchett turns the Pied Piper story on its head.

Maurice, a talking cat, leads a band of equally loquacious rats in a con game that spirals into a much bigger adventure.

“The Last Hero,” a beautifully illustrated novel, is an epic tale of Cohen the Barbarian and his Silver Horde setting off on one last quest – a quest that might just end the Discworld itself.

It’s a story of heroism, folly, and the poignant question of what happens to heroes when they grow old.

Finally, “The Shepherd’s Crown,” rounds off the Tiffany Aching series and the entire Discworld saga.

This final book, completed shortly before Pratchett’s death, is a fitting farewell, filled with heart, courage, and a testament to the enduring power of legacy.

Each standalone novel in the Discworld series is a tapestry woven with threads of satire, humour, and deep, abiding humanity.

They are stories that stand apart, yet are integrally connected to the intricate world Pratchett created.

Here, in these tales, we find the essence of Discworld – a reflection of our world, distorted and exaggerated, revealing truths we might have missed in the mundane.

These books, each a standalone journey, together form a rich, vibrant picture of a world we’re lucky to visit, one page at a time.

The Discworld’s enduring legacy

As we close the cover on the kaleidoscopic world of Discworld, what remains is not just the echo of laughter or the ghost of a grin, but a profound sense of having journeyed through a universe as vast and varied as our own.

Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series is not merely a collection of fantasy novels; it is a mosaic of satire, a tapestry woven with threads of sharp wit, deeper wisdom, and an unerring eye for the absurdities of human nature.

Through the bustling streets of Ankh-Morpork, the mystical depths of Lancre’s forests, the ethereal corridors of Death’s domain, and beyond, Pratchett has taken us on a tour de force of fantasy, humour, and satire.

We’ve met wizards of dubious competence, witches of formidable common sense, a city watch that holds a mirror to society, young witches finding their place in the world, a con artist turned civic hero, and seen the stirrings of an industrial revolution, each narrative pulsating with life and laughter.

The standalone novels, each a unique exploration of the Discworld, have shown us the power of story – to entertain, to enlighten, and to inspire.

From the parody of ancient civilizations to the slapstick of Hollywood, the satire of journalism to the poignant exploration of themes like war, identity, and the nature of heroism, these tales have expanded the Discworld universe in ways both hilarious and heartfelt.

Terry Pratchett’s Discworld is a microcosm of our world – a fantastical reflection where the ridiculous rubs shoulders with the sublime, where every joke contains a nugget of truth, and every absurdity a reflection of our own world.

It’s a place where satire is a lens through which we view our own follies and foibles, where fantasy is not an escape from reality but a funhouse mirror held up to it.

In the end, the Discworld series is more than just an entertaining fantasy saga.

It’s a commentary on life, a collection of philosophical musings disguised as comic fantasy.

Pratchett’s legacy is one of laughter and wisdom, a reminder that the world, be it round or disc-shaped, is a place of wonder, mystery, and endless possibility.

As we bid farewell to the Discworld, we do so with a smile and a tip of the hat to Sir Terry Pratchett, the man who created a world flat in shape but immense in its depth and imagination.

In these books, we find not just escapism but a celebration of humanity in all its glorious absurdity.

The Discworld may be a fantasy, but the truths it holds are as real as the pages we turn – a testament to the enduring magic of storytelling, and the enduring brilliance of one of the greatest storytellers of our time.

The post Exploring the Magic of Discworld: Terry Pratchett’s Fantasy World first appeared on Jon Cronshaw.